Pearl Harbor

December 5, 2019

Before the Bombing

It was only after the Pearl Harbor bombing that the FBI had realized that there were many spies set in Hawaii who were helping the Japanese. There were at least 4 spies helping the Japanese develop their elaborate plan to bomb the harbor. Their names were Takeo Yoshikawa, Harry T. Thompson, John S. Farnsworth, and Bernard Otto Kuehn. These 4 men were what caused America’s late involvement in World War II.

- Takeo Yoshikawa

- Takeo Yoshikawa was a Japanese spy who arrived at Hawaii in 1941. He took the name Tadashi Morimura so that his identity was protected in America. He stayed in Hawaii for nine months, making charts, giving details, and risking his life for the sake of some information. He would sometimes dress as a laborer and go on a minibus to the fields north of two bases. From those areas, he could see the submarine facilities at the Southeast Loch. A pier at Pearl City allowed the spy to see the far side of Ford Island and its air strip, but he was unable to see into the harbor due to both entrances of it being restricted. This did not stop him, though, because he used one or more of the consulate’s personnel to gather information. He had never illegally entered a base or stolen any documents. He only relied on his memory, avoiding cameras and other methods of taking photos. He and his helpers used the openness of America to gather information, and only did things legally. After he finished his mission in Hawaii, Yoshikawa went back to his home where he married and continued to work for naval intelligence. When U.S. Troops later occupied the land, he fled to the countryside and posed as a Buddhist Monk and returned home to his wife and children two years later. He hadn’t told the story to an American audience until 1960, 15 years after the incident.

- Julius Otto Kuehn

- Julius Otto Kuehn was a member of the Nazi Party, he arrived in Hawaii in 1935. By 1939, the FBI had already been suspicious of him. Despite his using a complex system of signals and codes, his contacts with Germany and Japan were enough to set them on edge. He also entertained U.S. Military Officials and expressed an interest in their work. Alongside this, he had two houses in Hawaii, lots of money, but no actual job. In November of 1941, Kuehn had offered to sell intelligence on warships in Hawaiian waters to the Japanese consulate in Hawaii. On December 2nd, 5 days before the attack, he provided detailed and highly accurate information on the fleet. It wasn’t until December 8th, the day after the attack, that Kuehn was arrested. He confessed to his crime and was sentenced to 50 years of labor instead of death by musketry, but was later deported.

- Harry T. Thompson

- It seems that Harry T. Thompson was one of the first spies to come to Hawaii, as he arrived before 1934. He had boarded many naval ships and obtained the schedules of employment of battleships and cruisers. He also gained information on torpedoes, main batteries, and related intelligence. As such, he boarded the USS Mississippi in December and managed to get a 230-page U.S. Navy gunnery school from a publication from a confidential file. Officials had followed Thompson for a while, gathered more evidence on him, and questioned him about his suspicious activities. It was at this point that Thompson confessed to spying. After this, the Office of Naval Intelligence attempted to get him to work as a counterspy. Thompson fled using the funds provided by the Japanese but was later apprehended and in mid 1936 he was found guilty of espionage before he was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

- John S. Farnsworth

- John S. Farnsworth was a 1915 graduate of the U.S Naval Academy. He commanded Marine Observation Squadron Six and the Aircraft Squadrons’ Scouting Fleet before he was relieved of command in 1927 and court-martialed. He was cited for drinking, gambling, and borrowing money from an enlisted man before refusing to pay it back.

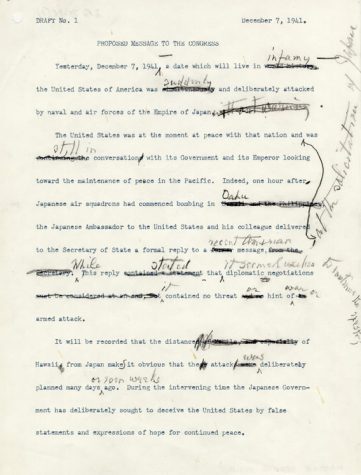

Just before Pearl Harbor was bombed, the U.S. received two communications from Tokyo sent to the Washington Embassy on November 19 that year. They held information on the Winds-message, and naval intelligence was alerted. The Winds-message was an instruction from Tokyo to Japanese legations worldwide that diplomatic relations were in danger of being breached. A few days before the tragic incident occurred, the U.S. had finally decoded the message, and every one had known that it meant-war.

Here is an excerpt on the winds-message from website warfarehistorynetwork.com:

“The first message, Circular No. 2353, said: “Regarding the broadcast of a special message in an emergency. In case of emergency (danger of cutting off our diplomatic relations), and the cutting off of international communications, the following will be added in the middle of the daily Japanese language short wave news broadcast:

In case of a Japan-US relations in danger HIGASHI NO KAZEAME––East Wind Rain.

Japan-USSR relations: KITANOKAZE KUMORI––North Wind Cloudy.

Japan-British relations: NISHI NO KAZE HARE––West Wind Clear.”

The second circular, No. 2354, came later:

“If it is Japan-US relations: HIGASHI.

Japan-Russia relations: KITA.

Japanese-British relations (including Thai, Malaya, and Netherlands East Indies): NISHI.

The above will be repeated five times and included at beginning and end. Relay to Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, San Francisco.”

The U.S. decrypted the code a little too late, as they had done it on December 4, 1941.

The Day of the Attack

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Japanese. World War II had currently been going in full force, and the U.S. hadn’t intervened until the bombing. That day, 2,403 people were killed and 1,143 people were wounded.

There had been several more concerning signals before December 7, but none of them had prepared the U.S. for what had come. On the night of December 6, the U.S. had decrypted yet another code and had forwarded their concerns to the Washington command, but they were not successful and the attack had begun.

The attack began at 07:55 in (military)Hawaiian time. It first began with aircrafts, then the ships in Pearl Harbor, the air stations at Hickam, Wheeler, Ford Island, Kaneohe, and Ewa Field were all attacked. It occurred for 2 hours and 20 minutes, but the damage continued to last.

“I hurried to a doorway on the harbor as the pilot of the plane got ready to launch his torpedo. I then went to a second floor armory to look for a weapon to fire at the planes. There were no weapons in the armory so I went to a window on that floor and witnessed the battleship USS Arizona blowing up. There was a tremendously loud explosion and a large column of water and material shot skyward. This column seemed to hang suspended for some time and then fell back downward. There were fire and flames all around battleship row at this time and Japanese planes were all over the sky. I saw two at the moment they were shot out of the sky.”

Chaos rang out through the harbor as torpedoes shot through the sky, machine guns rained bullets from the sky, and citizens frantically ran around, searching for refuge from the wrath of the Japanese. Many didn’t make it, and those who did were either severely injured or were believed to be dead until much later in December.

“At the office they stated that my parents had been notified by the Navy Department that I was missing in action. The Navy Department never notified my parents that I was okay. It was only when they received a personal letter from me December 23, 1941 that were they aware I had lived through the bombing at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.”

After the Bombing

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, there was much damage to be fixed. There had even been stray bombs, some of which were found by the citizens of Hawaii.

“One day while on duty at the Honolulu Police Station in the Shore Patrol office there I stepped out onto the sidewalk in front of the office to renew some black out paint on the windows of the office, when a boy of about 12 or 14 years of age rode up on a bicycle and pared it leaning on the wall between our office and the doorway into the area of the Military Police. The boy said to me, “I have some Japanese bombs in the basket on my bicycle.” I walked over, opened the bag and sure enough he had two shiny bombs with the fuses attached, and a button on the nose of each bomb. There was also an old looking bomb that appeared to be from World War I, about 25 years earlier. Just as I looked in at the bombs the phone in the Shore Patrol office rang and I told the boy to go see the Military Police next door. After I had answered the phone and at most only a minute or two later I came back out to where the bicycle had been and the boy, the bike, and the bombs were gone. Just then people came pouring out of every door in the building and onto

the street that ran alongside the building. I asked one person in a police uniform “what is going on?” He stated “a boy brought some Japanese bombs into the building and they are evacuating the building.” I hadn’t realized when I told the boy to go see the Military Police that he would take the bombs with him.”

It was on December 8, 1941 that the U.S. declared war on Japan, officially joining in on World War II. A mere 3 days later, Germany declared war on the U.S. on December 11, 1941.

All personal accounts are given by Andrew Hoover

Bombing of Pearl Harbor (1941)

“December 7th” (a 1943 John Ford film) and the real footage within – from THE EDUCATION ARCHIVE